International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women: Advocating for Our Patients in the #MeToo Era, by Anita Ravi

In July of 1981, activists at the first Feminist Encentro for Latin America and the Caribbean declared November 25th the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The day was originally selected to honor the Mirabal sisters, three Dominican feminists assassinated in 1960 for defying the Trujillo dictatorship, and to bring international attention to the pervasiveness of gender violence. [1]

In July of 1981, activists at the first Feminist Encentro for Latin America and the Caribbean declared November 25th the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The day was originally selected to honor the Mirabal sisters, three Dominican feminists assassinated in 1960 for defying the Trujillo dictatorship, and to bring international attention to the pervasiveness of gender violence. [1]

According to a UN report that gathered data from over 87 countries between 2005 to 2016, “…19 percent of women between 15 and 49 years of age said they had experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner in the 12 months prior to the survey.” [2] Ending gender violence is imperative to achieving reproductive freedom. For this year’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, RHAP is honored to feature Dr. Anita Ravi’s powerful article, “Advocating for Our Patients in the #MeToo Era.“

This article was originally published as a post in the American Academy of Family Physician’s Fresh Perspectives blog.

“Advocating for Our Patients in the #MeToo Era”

by Anita Ravi, MD, MPH, MSHP, FAAFP | Founder, Medical Director- The PurpLE Clinic at The Institute for Family Health | Assistant Professor- Department of Family Medicine & Community Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

The burden of fighting the culture of sexual violence does not and cannot lie solely on survivors. It must include the voices of physicians. The 2018 Nobel Peace Prize recipients offer a beautiful example of this dual effort. Denis Mukwege, M.D., Ph.D., and activist Nadia Murad — herself a survivor — were both recognized last week for their efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war.

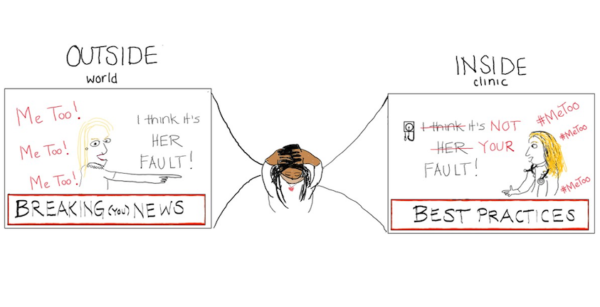

Three years ago, I started what you might call a #MeToo family medicine clinic. The PurpLE Clinic at the Institute for Family Health in New York, N.Y., was designed for people who have experienced sexual trauma, including sexual assault, domestic violence and sex trafficking. Every criticism from the outside world, from “Why didn’t she report it?” to “What if she’s lying?” can be answered inside the clinic. And yet, when I leave the confines of the medical space, I see these questions stubbornly fester in public discourse, exploiting the silence and circumstances of sexual trauma survivors.

As a doctor, I am compelled to counter the harmful misconceptions regarding sexual violence and trauma with truths that I have learned from clinical practice. Here are a few:

Story Telling

My clinical exam room is a graveyard of smashed stereotypes of what some people think victims should be — a distressed individual who provides a linear story with a desire to report the assault immediately.

Recounting a sexual assault is nonformulaic. Stories may come out as you make contact with the doorknob to leave the exam room, are about to begin a Pap smear, or have just placed a stethoscope on the heart. They may spill out hours after an assault or 20 years later. They may be the reason for a medical visit, or they may unexpectedly come up when you talk about diet and exercise and hear, “I tried to gain weight and stopped wearing makeup so I wouldn’t be raped again.”

As physicians, our responsibility to counter rape culture is not simply to share stories, but to share how our patients share their stories. We must lend credence to the unexpected smiles, inevitable gaps in memory and nonlinear information that is normal in trauma. The first sexual assault exam I ever did was with a teenage girl. She had never had a speculum exam. I asked if anything would make her feel more comfortable. She turned on her iTunes, and we started her exam with music blaring in the background. She had come in with her best friend. They laughed and giggled together. Her assault had occurred just seven hours earlier. That is trauma. Our public awareness must evolve to understand trauma’s permutations so survivors are not wrongly scrutinized.

Photos

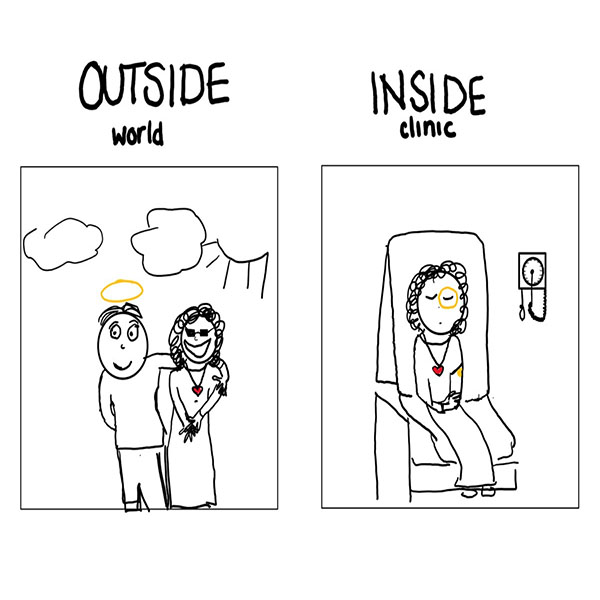

“But they looked so happy” is a common reaction when people learn that someone they know was in an abusive relationship. There are pictures seen by the outside world — images of a healthy, loving relationship, beautifully curated and filtered photos on Facebook and Instagram.

And then there are the photos I take in-clinic. Smiles to the external world are irrelevant in the confines of the exam room.

Every time I meet someone who has experienced a recent sexual assault or domestic violence, I ask two questions: “Do you plan to file a police report?” and “Would you like photos of the injuries in your medical record?” The answer is almost always “No” to the first and “Yes” to the second.

Every time I meet someone who has experienced a recent sexual assault or domestic violence, I ask two questions: “Do you plan to file a police report?” and “Would you like photos of the injuries in your medical record?” The answer is almost always “No” to the first and “Yes” to the second.

Photographing injuries remains a particularly unnatural and emotionally challenging part of my work. The silence during the 10-second process of setting up the camera always grows uncomfortably large. Sometimes she helps hold the ruler, noting my clumsy efforts to measure the injury while photographing. I press the button. And then I move to the next one. I hope that this process will never feel normal. And I hope that our public consciousness evolves to understand that the presence of happy pictures does not imply an absence of trauma.

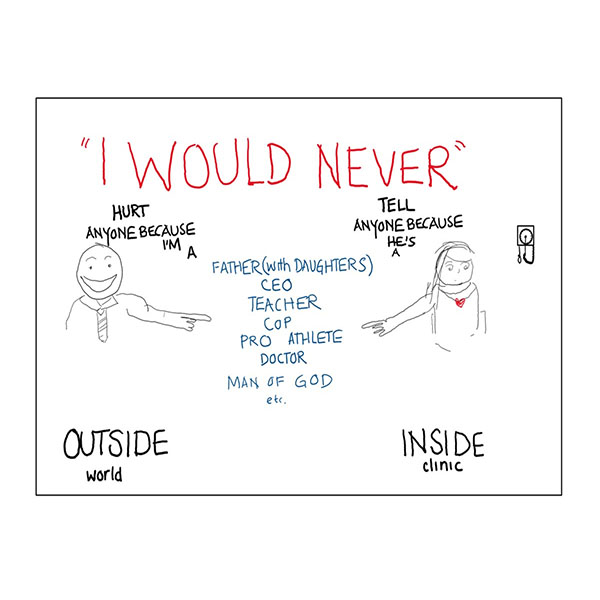

Résumés

Sexual assault is the abuse of power. It can be power based on many factors: gender, race, sexuality, immigration status, literacy, mental health, and on and on. When an accused person lists an illustrious resume, it tells me about their positions of power, but it does not tell me the responsibility with which they wield it. Being educated or wealthy is not a prophylactic against perpetrating violence. People in highly esteemed positions of power have hurt my patients. It’s a common reason that people don’t report the crime. In cases of sexual assault, résumés are not needed.

Résumés are also often used to highlight the harm to those who are accused of sexual assault. What if it’s not true? A person’s hard-earned standing in the world has been ruined. Look at what they’ve lost.

I wish this remarkable empathy could be applied in understanding the loss that comes with sexual assault. But it’s harder to quantify the loss of opportunities that were never actualized. In medicine, we are taught about “insensible losses” — the loss of fluids from our body that can neither be perceived nor measured directly but are critical to account for. Some sexual assault survivors experience a form of insensible loss on their résumés. The invasion of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety following sexual assault can result in life-altering changes that impact career trajectories. These are financial, physical and emotional losses that are masked by survivors’ resilience.

I wish this remarkable empathy could be applied in understanding the loss that comes with sexual assault. But it’s harder to quantify the loss of opportunities that were never actualized. In medicine, we are taught about “insensible losses” — the loss of fluids from our body that can neither be perceived nor measured directly but are critical to account for. Some sexual assault survivors experience a form of insensible loss on their résumés. The invasion of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety following sexual assault can result in life-altering changes that impact career trajectories. These are financial, physical and emotional losses that are masked by survivors’ resilience.

When asked about their dream job, my patients commonly respond, “I used to want to be X, but now I’d rather be Y.” X has included becoming a business owner, social worker or health professional, while Y has frequently included wanting to be a mortician or custodial worker — something quieter “where no one harasses you or tells you, ‘Your ass looks nice.’” These résumé changes often go undetected during the “inconvenience” of sexual assault accusation discussions, but it’s time for them to be accounted for and acted on in our collective response to sexual violence.

Witness

As each day of clinic wraps up and I step outside, two truths stubbornly, persistently demand my attention on my walk home: Sexual violence is a cultural infection, and adding physician voices is necessary for its eradication. Physicians bear witness to the patterns of stories that deserve to influence policies but may never be heard. The shared work of survivors and physician-allies is necessary to change our culture and to secure a future immune to sexual violence.